Herb of Love and Domination

Fragrant, vibrant, and deeply rooted in Italian tradition, basil is more than just an essential ingredient in the kitchen—it is a symbol of love, protection, domination, and prosperity. From ancient Roman rituals to the bustling markets of Sicily, this revered herb has played a role in both culinary and mystical practices. Whether woven into folklore as a token of affection, severed heads or infused into time-honored recipes, basil remains a cherished emblem of Italian heritage, carrying with it the soul of the Mediterranean.

Emotional and Psychospiritual Benefits Basil comes into our lives when we need to move and release internal obstacles to abundance. If we have grief from love lost or heartbreak that we have resisted feeling, basil can invoke the fire or inspiration, as well as confidence we need to allow the pain of loss to flow, resolve, and integrate as a natural consequence of being alive.

Fazio, Lisa. Della Medicina: The Tradition of Italian-American Folk Healing (p. 298). Inner Traditions/Bear & Company. Kindle Edition.

Isabella and the pot of basil (detail) William Holman Hunt • Painting, 1886, 186.7×115.6 cm

The Etymological Connection Between Basil and the Basilisk

The names basil (Ocimum basilicum) and basilisk (basiliscus) share a common root in the Greek word “βασιλεύς” (basileus), meaning “king.” This connection is no coincidence, as both the herb and the mythical creature were associated with power, dominion, and the forces of life and death… Click to Purchase Basilicum—The Ancient Basil Oil of Ancient Greece & Rome ➜➜➜

Basilisk: The “Little King” of Serpents

The term basilisk comes from the Greek “βασιλίσκος” (basilískos), meaning “little king” or “prince,” referring to the belief that this serpent ruled over all other snakes and venomous creatures. The basilisk was a creature of deadly sovereignty, its gaze capable of killing, its breath able to poison the very air. It was thought to be hatched from a serpent’s egg incubated by a rooster, an unnatural combination of opposing forces.

In medieval bestiaries, the basilisk was often crowned, reinforcing its royal and fearsome nature. Some traditions even claimed it could only be defeated by the weasel or by its own reflection, echoing myths of prideful rulers brought down by their own hubris.

Basil: The Royal Herb

Basil, too, derives from “basileus” (king), and was often called the “king of herbs.” Some sources suggest that basil was so named because of its high value, rarity, and sacred uses in ancient cultures, while others link it to the belief that basil was an antidote to poisons, including the basilisk’s venom.

Throughout history, basil has been associated with divine favor, power, and mysticism:

- In ancient India, basil was sacred to Krishna and Vishnu, used in spiritual protection and healing.

- In Greece and Rome, basil was linked to wealth, love, and warding off evil—it was often planted with ritual invocations to ensure its potency.

- From Lazio, where my bisnonna descended, she taught that every plant has a spirit and that when planting, offerings of eggshells and dead fish are given in the soul. To commune with the plant, you must uproot it and “wash la faccia” (its roots) and speak to it your intentions. As it grows, your intentions are carried by the plant, if the plant dies or wilts, your intention will not be met or is impeaded by other forces at work.

- In medieval Europe, basil was believed to have protective properties against venomous creatures, particularly snakes and scorpions—a direct parallel to its etymological twin, the basilisk.

Basil and the Basilisk: The Duel of Kings

Given their shared etymology and mythological significance, basil and the basilisk can be seen as opposing yet intertwined forces—one ruling over life, healing, and love, the other reigning over death, destruction, and poison.

- Basilisk represents unchecked power, fatal arrogance, and the dangers of corrupt rule.

- Basil is the antidote, a controlled power wielded for protection, love, and restoration.

This connection reinforces ancient beliefs in the duality of forces—the need for an opposing power to counterbalance a destructive one. Just as light balances darkness, basil is believed to neutralize the basilisk’s poison, making it both the herb of kings and the herb that slays the king of serpents.

Basil and Sicilian Culture: The Sacred Myth of Mata and Grifone

In Sicily, basil is more than just an aromatic herb—it is a symbol of passion, transformation, and power, deeply tied to the island’s folklore and traditions. One of the most striking connections is found in the legend of Mata and Grifone, the towering figures who represent the mythological origins of Messina.

Basil, often associated with love and devotion, finds its place in this tale as a metaphor for their union. In Sicilian tradition, basil has long been seen as a plant of both passion and mourning—a symbol of love that transcends barriers, much like the story of Mata and Grifone. Some believe that women would place basil on their windowsills as a sign of affection, a silent invitation for a suitor’s love, while others see it as a reminder of the deep-rooted connections between Sicilian identity and its multicultural past.

According to the legend, Grifone was a Saracen warrior who arrived in Sicily during the Arab invasions. Mata, a noble Sicilian woman, perched on her balcony, the most beautiful woman of the land, growing herbs and fruits of every variety. At first sight, Grifone fell in love with her—Mata’s beauty and fierce spirit captivated him. He proposed to her immediate from the street and announced his proposal to her on her balcony. He abandoned Islam and converted to Christianity, and vowed to be with her forever.

On another layer of the tale, their union symbolizes the blending of cultures that defines the island. The ritual of the balcony proposal is also defined by Italian culture in the Festival of li Schietti, celebrated on Easter weekend. A test of strength where the young schetto (bachelor) shows off his stamina in order to impress a woman for marriage rites.

However, one night he told Mata that he could not stay with her any longer. She demanded an explanation for this sudden statement of abandonment. He told her that he had a wife and children back in Africa already, and he needed to see them but he would return. Furious at this reality, Mata went into a bloodlust rage and grabbed her sword! They dueled in a lovers quarrel and in the end, Mata decapitated the head of Grifone as she was a formidable warrior. Some versions tell of her cutting off his head in the night in a final act of vengeance. To ensure his soul would never escape her grasp, she stuffed his severed head with basil, a plant known in Sicily not only for love but for domination and binding magic. She cursed him to remain with her forever—not in life, but in death.

This version of the legend ties into an old Sicilian tradition: the Testa di Moro (Moor’s Head) ceramic planters, which often depict a severed Saracen head overflowing with basil. These planters, still found on balconies throughout Sicily, serve as a reminder of this tale—a story of conquest, love, and ultimate revenge. Basil, in this sense, becomes a plant of both passion and control, symbolizing not just romance but the power to hold another’s soul in eternal captivity.

Even today, during the Festivals of the Giganti in Messina, the towering figures of Mata and Grifone parade through the streets, echoing the legendary past where love, transformation, and vengeance intertwined. Just as basil remains a powerful herb of love and command in Sicilian folklore, so too does the legend of Mata and Grifone remind us of the complex and mysterious history that shapes the island’s soul.

Mata and Grifone, Hades and Persephone, and the Basil Connection

The legend of Mata and Grifone, the giant founders of Messina, echoes a tale as ancient as time—the abduction of a woman by a powerful figure, love forged in captivity, and the transformation of this union into legend. Their story is often told as one of conquest and reconciliation, but beneath the surface, it carries the deep mythological echoes of Hades and Persephone, with basil as the herb of both love and death, binding souls together in the afterlife.

Mata and Grifone: The Sicilian Giants

According to legend, Mata, a beautiful Sicilian woman of noble Christian blood, lived in Messina when Grifone, a Saracen warrior-giant, arrived with invading forces. He was a man of immense strength, and upon seeing Mata, he desired her. But Mata rejected him, remaining steadfast in her faith and resisting his advances at first.

Determined to possess her, Grifone attempted to captivate Mata. But rather than simply force his will upon her, he tried to win her love, even converting to Christianity to prove his devotion. Eventually, Mata accepted him, and their union symbolized the merging of different cultures—Saracen and Sicilian, pagan and Christian, Europe, Middle East and Africa. Today, their figures are still celebrated as “I Giganti” (the Giants) in the processions of Messina.

However, an older, darker version of their story lingers beneath the surface—one that mirrors the ancient myth of Hades and Persephone.

Hades and Persephone: Love, Abduction, and the Binding of Souls

In Greek mythology, Hades, god of the underworld, fell in love with Persephone and abducted her, taking her into his dark kingdom. Persephone, initially a captive, eventually came to rule beside him, but only after eating pomegranate seeds, which bound her to the underworld.

The echoes between this myth and Mata’s story are clear—she is a woman taken advantage of, albeit in a different form, but through time and transformation, she becomes forever linked to the very force that once entrapped her.

Basil: The Herb of Love, Death, and Domination

Basil (basilico) plays a profound role in both Sicilian folklore and the Persephone myth. It is an herb of love and possession, used in spells of attraction and to keep a lover’s spirit bound. In some traditions, basil was planted on graves or in the hands of the deceased for protections, connecting the souls of the living and the dead, ensuring that the deceased would never be forgotten.

When Mata kills Grifone, cutting off his head and stuffing it with basil, she ensures that his soul will remain bound to her forever, even in death. This is eerily similar to the story of Isabella and the Pot of Basil from Boccaccio’s Decameron, where a woman buries her lover’s severed head in a pot of basil, watering it with her tears—-In this act, she activates and binds the spell.

Basil, in this sense, is both a lover’s herb and a mourner’s herb, symbolizing the inescapable connection between passion and fate. Just as Persephone is forever tied to Hades via the pomegranate, Mata—through basil—binds Grifone to her in death, ensuring that his spirit remains captive in her memory and in the soil itself.

The Unbreakable Bond: Basil, Giants, and the Underworld

Both Mata and Persephone represent the divine feminine—women who are taken by powerful men, but who ultimately gain power over them. Mata’s use of basil implies that she is victorious over him—much like Persephone, who becomes Queen of the Underworld, ruling alongside Hades rather than beneath him. Just as Persephone is Queen of the Underworld, so to is Mata Queen. Mata is sometimes referred to as “The White Queen of the North” while Grifone is sometimes referred to as “The Black King of the South”. Esoterically representing the union of opposites, “as above, so below”.

Basil remains the connecting thread, symbolizing:

- Love that transcends death (as in funerary rites)

- Binding and domination (used in folk magic to control a lover)

- Mystical transformation (as in the connection between Mata’s basil and Isabella’s pot of basil)

Even today, the Giganti of Messina are paraded through the streets, larger than life, like lingering spirits who refuse to fade. Their story, like the myth of Hades and Persephone, continues to be told, carried on the scent of basil—an herb that bridges love and the afterlife, the past and the present, the conqueror and the conquered.

Basil, Tarantismo, and the Awakening of the Tarante Spirits

Basil, with its heady, aromatic scent, has long been associated with mystical rites, transformation, and spiritual awakening in Italian folk traditions. In the ancient practice of Tarantismo, the frenzied dance ritual used to exorcise the bite of the mythical tarantula, basil held a unique and potent role—not just as a medicinal herb but as a spiritual stimulant that could provoke the restless spirits of the Tarante.

In Italian folk belief, particularly in Southern Italy, the Tarante was not merely a spider or other totemic animals but a possessing force, a spirit, an ancestor, that could induce uncontrollable dancing, visions, and trancelike ecstasy. Those who had fallen under its power—often women known as tarantate—could only be cured through music, dance, and specific scents that stirred the spirit into revealing itself. Among these, basil was one of the most powerful.

The pungent, almost intoxicating aroma of basil was believed to awaken the spirit of a Taranta, drawing it out of the afflicted and pushing them deeper into their frenzied movements. The scent, often intensified by crushing fresh basil leaves as an aromatic stimuli, used alongside tambourines, violins, and frenzied rhythms to heighten the ritual’s intensity. Just as the music dictated the movements of the tarantate, the scent of basil acted as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds, ensuring the dancer reached the necessary climax of their trance.

Furthermore, in traditional Italian magical practices, basil was known as an herb of heat, fire, and stimulation, often used in love spells, exorcisms, and rituals of protection. These beliefs were influenced by Renaissance Humoral Medicine associations and correspondences. It was said that basil could attract spirits, particularly those that needed to be tamed or appeased. In the context of Tarantismo, it was thought to provoke the hidden forces within the afflicted, forcing the spirit to either manifest fully or be expelled through the exhausting dance.

Though Tarantismo as a formal practice has faded (we are reviving it!), the folk memory of basil as an herb of movement, transformation, and spirit possession remains deeply embedded in Italian mystical traditions. Whether in love magic, ritual dance, or the lingering scent of basil in the air, its power continues to echo through time, much like the relentless rhythm of the Tarantella itself.

During the Renaissance, basil was more than just a culinary herb—it was deeply intertwined with folklore, medicine, and astrological beliefs. Physicians and herbalists of the time, drawing from ancient Greek, Roman, and medieval sources, considered basil both a healing plant and a potential source of harm, particularly in relation to the astrological sign of Scorpio and the dreaded idea of scorpions growing in the brain if too much was smelled!

Basil, Scorpio, and the Scorpion in the Brain

Basil was frequently associated with Mars and Scorpio, two powerful astrological forces linked to passion, war, and transformation. In Renaissance thought, herbs were often assigned planetary rulership, and basil’s fiery, pungent nature aligned it with the intensity of Scorpio. This sign was connected to hidden forces, poisons, and even the power of resurrection—fitting for an herb that symbolized both love and death.

One of the most persistent beliefs of the period was the strange yet widespread fear that smelling basil could cause scorpions to form in the brain. This idea, with origins in classical antiquity, was perpetuated in Renaissance herbal texts. The notion stemmed from observations of scorpions nesting under basil pots and from Galenic medical theories, which suggested that strong-smelling substances could influence the humors and provoke dangerous conditions. Some believed that prolonged exposure to basil’s scent could generate scorpions within the skull, leading to madness or death. The 16th-century herbalist Pietro Andrea Mattioli noted that some people feared basil’s ability to attract scorpions or even transform into one when crushed.

Despite these superstitions, basil was still highly valued for its medicinal and magical properties. It was used in love spells, funerary rites, and protection against venomous creatures—ironically, including scorpions. In some cases, it was believed that placing basil on a wound from a scorpion sting could draw out the venom.

Basil: Love, Death, and the Underworld

Beyond its connections to Scorpio, basil was also linked to themes of love and mourning. In Italy, it was associated with both passionate romance and tragic loss. Stories like the Sicilian legend of Isabella and the Basil Pot—where a woman kept her murdered lover’s head hidden in a pot of basil—reinforced the herb’s dual nature as both a symbol of devotion and a marker of grief.

Thus, in the Renaissance, basil was a paradoxical plant: loved for its culinary and medicinal uses, feared for its supposed connection to scorpions, and revered for its ties to love, death, and transformation… and today in a great Italian Sunday sugo!

Boccaccio’s Pot of Basil & Its Connection to Mata and Grifone

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353) is a masterpiece of medieval Italian literature, filled with tales of love, tragedy, and human folly. One of its most haunting and enduring stories is that of Elisabetta da Messina and the Pot of Basil, a tale of forbidden love, grief, and the dark connection between love and death. This story resonates deeply with Sicilian folklore, particularly the legend of Mata and Grifone, and their entangled themes of power, conquest, and undying bonds—even in death.

The Tragic Tale of Lisabetta and the Pot of Basil

In The Decameron (Fourth Day, Fifth Story), Lisabetta, a young woman from Messina, falls in love with a man named Lorenzo, a merchant in the service of her wealthy brothers. When her brothers discover the affair, they see it as dishonorable and murder Lorenzo in secret, burying his body in the forest. Distraught over his sudden disappearance, Lisabetta eventually has a dream in which Lorenzo’s ghost reveals his fate and tells her where to find his body.

She ventures into the woods, unearths his remains, and in her desperate grief, severs his head and brings it home. She places it in a pot of basil, watering the plant with her tears. The basil flourishes, fed by her sorrow, and becomes an object of her obsessive mourning. Her brothers, suspicious of her behavior, steal the pot and discover the gruesome secret. Overcome with grief, Lisabetta withers away and dies—another victim of love’s cruel fate.

Basil: The Herb of Love and Domination

Basil, known in Italian folklore as an herb of love, plays a central role in both stories. It symbolizes devotion, but also power over the dead. In the case of Elisabetta, the basil pot becomes a mourning relic, keeping her love alive beyond the grave. For Mata, basil acts as a tool of domination, ensuring that Grifone’s spirit is forever linked to her.

In Sicilian tradition, basil has long been associated with both love and death. It was placed on windowsills by women to signal their romantic interest, but it was also used in funerary rites, believed to protect the spirits of the dead. In this way, both Elisabetta and Mata use basil as a means to control fate itself, binding their lost loves to them even beyond the veil of death.

The parallels between The Decameron‘s Pot of Basil and the legend of Mata and Grifone highlight a recurring theme in Sicilian and Italian storytelling: love and death are inseparable, and the bonds we forge in life may persist beyond the grave. Whether in a medieval novella or in the folklore of Messina, the image of a severed head cradled in a basil pot remains a chilling reminder of how passion, vengeance, and grief can intertwine—creating legends that endure for centuries.

“Quantu Basilico” by Rosa Balistreri: A Song of Love, Power, and Mysticism

https://www.culturasiciliana.it/20-rosa-balistreri/le-canzoni-inedite/629-quantu-basilico-castelli

Rosa Balistreri, one of Sicily’s most powerful voices in folk music, sang with raw emotion, carrying the weight of Sicilian history, suffering, and spirituality in her melodies. Quantu Basilico is a song steeped in poetic imagery, using basil as a symbol of love, devotion, and even mystical power.

The Symbolism of Quantu Basilico

Basil (basilico) has deep roots in Sicilian and Mediterranean folk tradition, where it represents love, protection, and even domination over the beloved. The song begins with the imagery of sowing basil, suggesting both the cyclical nature of love and the active cultivation of desire and connection. The phrase “Tu devi darmene un pezzettino al giorno” (You must give me a little piece of it each day) speaks to the idea that love is not just a grand passion but something that must be nurtured and exchanged in small, daily acts.

In Sicilian folklore, women would place basil pots on their windowsills to attract suitors, as the scent was believed to stir passion and devotion. At the same time, basil has ties to funerary rites and the dead, linking it to love beyond death—a theme seen in legends like Lisabetta and the Pot of Basil from Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Love, Power, and the Spiritual Exchange

The song continues with the offering of the heart:

“Ah! Se vuoi il mio cuore te lo mando, il tuo dovrai mandarmi di ritorno.”

(Ah! If you want my heart, I will send it to you, but you must send me yours in return.)

Here, love is portrayed as a binding contract, an exchange of hearts that mirrors spiritual and magical traditions where love is sealed through reciprocal offerings. This reflects the belief that love, when true, must be an equal exchange of souls—otherwise, one risks imbalance, longing, and even spiritual suffering.

Basil’s Connection to Sleep, Dreams, and the Spirit World

The line “Le tue carni tenere fanno profumo che a chi le odora passa il sonno” (Your tender flesh gives off a perfume that, to those who smell it, takes away sleep) introduces a mystical connection between love, scent, and wakefulness. In Sicilian and southern Italian magical traditions, love and sleep deprivation are often linked—love-sick individuals are said to be haunted by the presence of their beloved (unrequited love—a cause of becoming Tarantati), unable to rest. Basil, with its strong fragrance, is sometimes used in love spells to keep one’s lover constantly thinking about the other, ensuring their devotion through obsession.

This idea also recalls the traditions of Tarantismo, where music and scent were believed to provoke spirits, awakening something primal within the soul. Basil, like the music of the Tarantella, has the ability to stir restlessness and longing, drawing the beloved deeper into the spell of love.

The Libertine Spirit of Love

The final verse of the song brings an almost libertine conclusion:

“Ah amore mio! ah! Se ti avessi al mio comando, domani mi alzerei a mezzogiorno.”

(Ah, my love! Ah! If I had you at my command, tomorrow I would wake up at noon.)

This suggests the joy and freedom of indulgence, breaking away from rigid expectations of duty and structure. The idea of waking at noon signifies a life dictated by passion rather than obligation, embracing love and sensual pleasure as guiding forces. This mirrors ancient Dionysian themes, where love and ecstasy overthrow the mundane structures of life. The “Libertine” is also a Taranta spirit of the same nature.

A Song of Mystical Love

Quantu Basilico is more than just a love song—it is a folk incantation, a poetic spell of devotion and control, carrying the weight of Sicilian traditions where love, magic, and nature are inseparable. Through its use of basil as a symbol of passion, spiritual binding, and mystical influence, the song echoes deep Mediterranean beliefs about the power of scent, the exchange of hearts, and love as both an intoxicating freedom and a binding force. Rosa Balistreri, with her haunting voice, transforms this simple folk melody into a sacred invocation of love and destiny, keeping alive the spiritual and magical heritage of Sicily.

Stregoneria and Basil

Excerpt from The Picatrix, pg. 284:

(The Picatrix was a medieval book of magic, astrology, and alchemy that was translated into Latin and read in Italy by scholars such as Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola.)

For making green tarantulas that kill by biting. When you want to do this, fast for a whole day until nightfall. At night, take the herb called wild basil, which you should chew well; and put what you have chewed into a glass jar, the mouth of which you should seal well. Put it in a dark house where neither the sun nor any other light is visible, and let it stay there for forty days. Then take it from there, and in it you will find green tarantulas which, if they bite any man, they will kill him. These tarantulas have a property: if you put them in olive oil in the sun, and let them stay there for 21 days or some similar time, they will die and be dissolved into the oil. If you anoint tarantula bites with that oil, they will be healed; and if a drop of it falls on a tarantula, it will die in an instant.

Excerpt from The Folklore of Plants by Albert R. Mann, pg.108

In Italy, Basil is considered potent to inspire love, and its scent is thought to engender sympathy. Maidens think that it will stop errant young men and cause them to love those from whose hands they accept a sprig. In England, in olden times, the leaves of the Periwinkle, when eaten by man and wife, were supposed to cause them to love one another. An old name appertaining to this plant was that of the ” Sorcerer’s Violet,” which was given to it on account of its frequent use by wizards and quacks in the manufacture of their charms against the Evil Eye and malign spirits. The French knew it as the Violette des Borders, and the Italians as Centocchio, or Hundred Eyes.

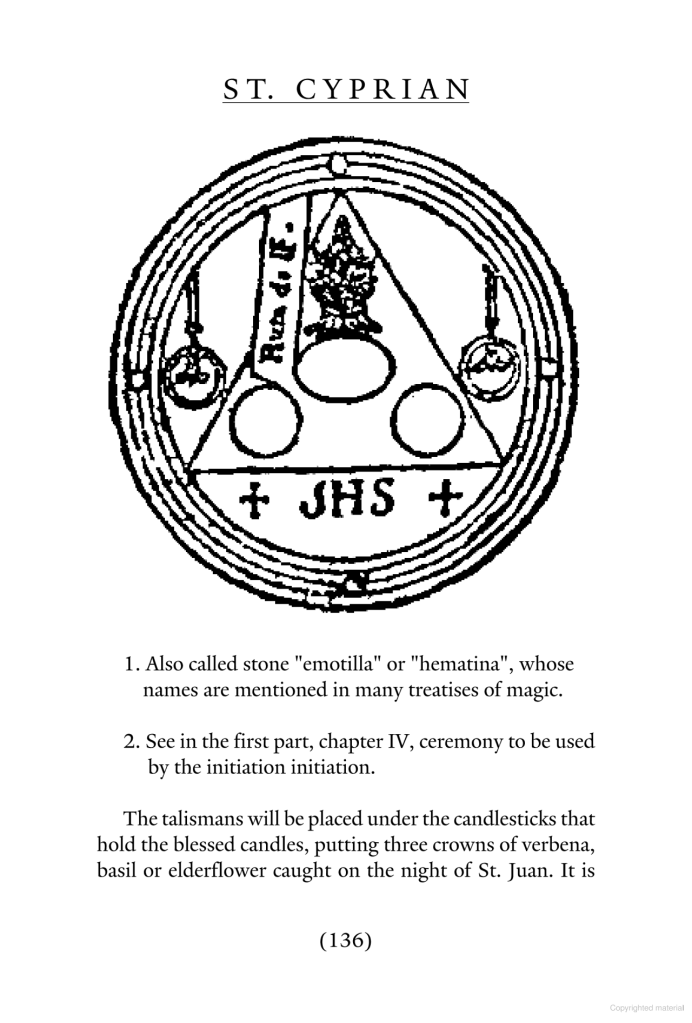

The Grimoire of St. Cyprian, English Edition By Edmund Kelly · 2019

(From the Grimoire of Saint Cyprian, created in the 19th century from a Medieval lineage of source work.)

The talismans will be placed under the candlesticks that hold the blessed candles, putting three crowns of verbena, basil or elderflower caught on the night of Saint John.

This relates to several other traditions in Italy such as L’Acqua di San Giovanni (Saint John), who’s herbs and water must be picked and created on the morning of Saint John’s day. This was also an important night and day of the Streghe as recorded in the inquisition. Basil is also used among Arbëreshë communities in Italy as part of Christian Orthodox ceremony and its use as as an aspergillum to be used with holy water.